Interview with Deborah Ruiz Wall – Reimagining Australia

Deborah Ruiz Wall (OAM) is a Filipino-Australian born in Manila who I met at Reimagining Australia, her exhibition at the WA Maritime Museum. The exhibition is based on her research on interactions between Filipino and Australia’s First Nations People.

Before she migrated to Australia, Deborah worked as a journalist with the Philippine Broadcasting Service in 1970 and as Press Secretary for the Opposition Leader, Matthias Toliman and later for his successor,Tei Abal in the Papua New Guinea House of Assembly in 1973. When she moved to Australia, she taught communication and social sciences TAFE (NSW). She completed oral history projects that included Redfern Oral History and story sharing between Aboriginal and Filipino women in inner-city Sydney. In 2004, Deborah was awarded an OAM for her contribution in areas of social justice, multiculturalism and reconciliation. Deborah’s stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people of Filipino descent that resulted in the publication of the book Re-imagining Australia (co-authored by Christine Choo) and international museum exhibits, including the WA Maritime Museum one. She is also a published poet.

The wizard wind carries lonesome melodies

echoing memories of the past hundred years —

of schooners, luggers, pearl shells,

and waves of settlers called Manilamen,

washed ashore in the Torres Strait and Broome— “Manila Men – The Outsiders Within”

What was your most exciting discovery? My most exciting discovery is the immense impact of institutional governance on the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians and Australians of Asian backgrounds dating back from pre-Federation times. The colonial footprints of a race-based rule had not entirely faded away. As the former Race Discrimination Commissioner Tim Soutphommasane puts it, “Whiteness in Australia involves a hierarchy of belonging…(and) is systemic and institutional”. I myself would like to feel a deep emotional sense of ‘Belonging to Country’ — to Australia, my home for the last 45 years. I have two children, one born in Manila; the other, born in Sydney. Their father, my late husband, of Anglo-Australian and quarter French background, was born in Melbourne.

My awareness of the power of Legislative Acts stemmed from my PhD research that included the impact of laws on Aboriginal people’s native title rights as a consequence of a mining development proposal in the Kimberley.

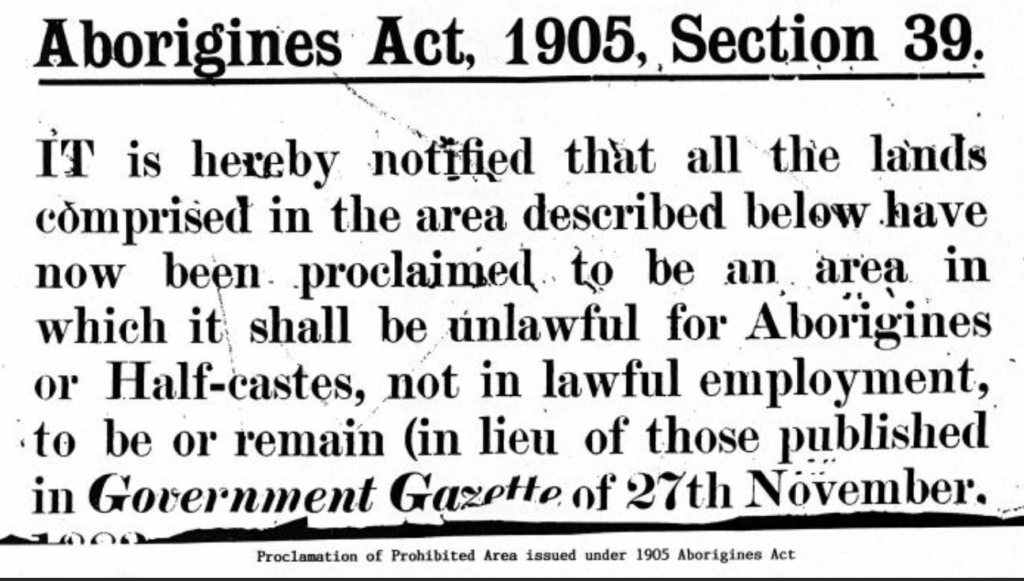

I re-directed my attention on laws from the governance of a development issue to the history of the settlement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders of Filipino descent from the time of the arrival of Manilamen in Australia. When the government introduced Pearlshell Fishing Regulation 1871 and Pearlshell Fishery Regulation Act 1873 to regulate the engagement of Aboriginal people and to protect them from gross abuse in the industry, an acute shortage of labour occurred. The labour shortage paved the way for the importation of indentured Asian workers for the pearling industry. Manilamen were among the recruits that included Chinese, Malays, Koepangers and others. Another law introduced after Federation, the Aborigines Act 1905 barred Aboriginal people’s access to towns between sunset and sunrise, forcing them to live in reserves outside towns and giving the Chief Protector the right to remove Aboriginal adults to any district if he believed it was in their interest to do so. This Act also prohibited co-habitation between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people.

What I found upon my arrival in Broome surprised me.

What inspired Re-imagining Australia? Being a naturalised Australian is not just about possessing a ‘Certificate of Australian Citizenship’. I wanted to feel a deep emotional sense of ‘Belonging to Country’. When I heard about interactions between Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people of Filipino descent, I was delighted and was determined to pursue their story. I already completed three oral history projects involving Aboriginal and Filipino people in Sydney. To explore the stories of Indigenous Australians of Filipino descent was a calling that I could not resist.

What inspired Re-imagining Australia? Being a naturalised Australian is not just about possessing a ‘Certificate of Australian Citizenship’. I wanted to feel a deep emotional sense of ‘Belonging to Country’. When I heard about interactions between Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people of Filipino descent, I was delighted and was determined to pursue their story. I already completed three oral history projects involving Aboriginal and Filipino people in Sydney. To explore the stories of Indigenous Australians of Filipino descent was a calling that I could not resist.

In 2007, I took the opportunity of meeting the Pigram Bros, an Aboriginal musical band of Filipino descent. After interviewing them for an article, Stephen Pigram, a singer song-writer passed onto me his relative’s name, Kevin Puertollano. He said that Kevin would be the best person to introduce me to the Filipino-Aboriginal community in Broome. It so happened that Broome was chosen to be the venue for the National Oral History Conference in 2008. I gave a talk at that conference about the result of my oral history projects in Redfern and Fairfield [Sydney, NSW].

In 2007, I took the opportunity of meeting the Pigram Bros, an Aboriginal musical band of Filipino descent. After interviewing them for an article, Stephen Pigram, a singer song-writer passed onto me his relative’s name, Kevin Puertollano. He said that Kevin would be the best person to introduce me to the Filipino-Aboriginal community in Broome. It so happened that Broome was chosen to be the venue for the National Oral History Conference in 2008. I gave a talk at that conference about the result of my oral history projects in Redfern and Fairfield [Sydney, NSW].

After the conference, I stayed in Broome for three months. My intention was to develop a personal relationship with prospective narrators and obtain their permission to record and publish their stories in a book.

What I found upon my arrival in Broome surprised me. I found three waves of Filipino settlers: the ‘first wave’ — the descendants of seafarers from the Philippines, who arrived in Australia from the late 1860s; the ‘second wave’ — Australians who married Filipino women from the 1980s onwards; and the ‘third wave’ — 457 Filipino visa holders who arrived from around the 1990s on work contracts.

I decided to focus on the ‘first wave’. At that time, hardly anything was known about the Philippine-Australian story as told by Australian Aboriginal-Filipino descendants. This project conjured a feeling of an impending discovery of the footprints of Australia’s historical ‘DNA’ linked to the Philippines, my place of birth. It inspired me to write my book.

I’m really fascinated by movements by Asian and Pacific Islands people in the 19th Century. How challenging was it for you to trace individual migratory pathways? I have benefited from the work of historians such as Filomeno Aguilar, Reynaldo Ileto and Rodney Sullivan and from the narratives of the Manilamen descendants from Broome and Torres Strait. Combining and connecting these two narratives provides us a more comprehensive picture of their Australian story.

As an “Insider”, it was easier to gain the trust of the Manilamen descendants because of our shared ancestry and history. We were able to exchange information that was mutually beneficial about each other’s shared culture even though we were dealing with different periods and different locations. Proficient in both Tagalog and English, I was able to provide some linguistic and cultural clues related to their forebears’ lives. An older narrator used to call me “Countryman” a term they had themselves used to refer to those of common Filipino ancestry in their own community—a sense of their strong cultural identification.

West Australian history is far more interesting than what is taught in schools. I was blown away by the number of Asians and Aboriginal people living in Broome in the late 19th Century, and that they far outnumbered the white settlers. Have you presented your research to schools or developed teaching resources? Developing new teaching resources for schools really need to be done. Maybe someone else can do this.

Has anyone approached you or have you thought about adapting Re-imagining Australia for the screen? I can see it as a Netflix documentary! I can also see it as a historical feature film or TV mini-series! Many possibilities. Mitch Torres, a film maker and a narrator in our book, can do this.

In the 1990s you produced Dealing with the Media to help community workers deal with journalists who often used the mail-order stereotype to depict Filipino women. What sort of strategies were there and how challenging was this, given that around that time there were only one-dimensional representations of Asian women in Australian public domain? My approach with the resource Dealing with the Media was to do a content analysis of the media presentation of Filipino women in Australia. John Mowatt and I developed a training manual for community workers to help them when they are approached by journalists for an interview so they can develop strategies to avoid the pitfalls of misrepresentation, sensationalism and stereotyping of Asian women in relationships with Anglo Australian and men of European background. The ‘mail order bride’ stereotyping including the film, Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, was a glaring example.

What’s next? I am doing the stories of two Aboriginal elders in Sydney: Aunty Beryl Van Oploo and Aunty Ali Golding for the Women’s Reconciliation Network. When this is completed, I will do my own ancestral research —I began gathering information in Angono, Rizal for three months in 2018—. Very rich history from the 19th century. It’s been put in the back burner at the moment.

Deborah Wall (Official Website): https://debrwall.wordpress.com/