Famous Adopted People: a Novel – by Alice Stephens

I saw Famous Adopted People at my local library and picked it up for a friend who has an adopted child. I was in a hurry so I didn’t see the words ‘a novel’ and thought it was a non-fiction book about famous adopted people.

It is not.

The book is best described as a rollicking read that explores a range of salient issues around transnational adoption and one that exemplifies how some truths are best told through fiction.

At the start of the novel, we meet two young women who are negotiating the complexities of their transnational and racialized identities. At the center of the story is Lisa Pearl, a Korean-America adoptee who isn’t particularly interested in finding her biological mother but is roped into it by her best friend Mindy, also a Korean-American adoptee. Mindy, whose adopted parents are WASPs, is a successful doctor engaged to Trip, a lawyer from the same upper echelon of society. Finding her birth mother will complete Mindy’s seemingly perfect life. In contrast, Lisa’s was adopted by a now divorced Jewish couple and her most recent relationship was with a student in Japan, where she’s been living. Lisa has reservations about finding her birth mother yet Mindy talks her into heading over to Seoul to work with MotherFinders. Mindy is excited by the prospect of finding and meeting her biological mother, whereas Lisa is more interested in Harrison, a handsome man who works for the agency. After a heated argument with Mindy, Lisa decides to head back to the US to lick her wounds as her career in Japan has been compromised by her inappropriate relationship with the student. Unable to get an immediate flight back, Harrison (now known to her as Ji-Hoon) suggests that Lisa joins him on a mini-break to a nearby island. This is where the book takes an unexpected turn that is both dark and hilarious.

After I finished reading the book, I wrote to the author Alice Stephens, to tell her how much I enjoyed her book, and I was thrilled when she agreed to an interview!

I wanted to write a novel that dealt honestly with the sensitive subjects of family and race while making the adoptee the hero of her own story.

Born in South Korea to a Korean mother and an American soldier father, Alice was adopted at 9 months old into a white family from Philadelphia with three biological children. The family moved to Botswana when she was four. Alice’s work has appeared in Urban Mozaik, Flung Magazine, Banana Writers, The American, the LA Review of Books, and the Washington Independent Review of Books. Famous Adopted People is her debut novel.

Firstly, congratulations on getting your book published and thank you for writing it. I picked it up from my local library from the “New Books” section thinking it was a collection of profiles about famous adopted people What I loved so much about it is that it deals with the complexities of transnational adoption in a serious, satirical and thoroughly engaging way. I laughed out loud in some parts of the book and then was deeply disturbed in other parts. Thank you! I am so delighted that you randomly picked my book up at the library and loved it so much you got in touch with me. I love that Famous Adopted People made it to a library in Australia! As an avid library user, it thrills me that people are discovering my work through their local libraries. And an author always loves to get positive feedback on her work, to know that she has touched somebody’s life in a positive way. So thank you very much for reaching out to me, and for this interview!

What inspired you to write this book? The subject of transracial adoption has been something of a trend recently in novels, and I was frustrated that most of the books seemed to tell the same exact story over and over again, as if there was only one story to be told about adoption. In these stories, the adoptee is basically passive, waiting for someone—usually the adoptive parents or birth mother—to rescue her. So I wanted to write a novel that dealt honestly with the sensitive subjects of family and race while making the adoptee the hero of her own story. In my novel, the only person who can save the adoptee is the adoptee herself.

How long did it take you to write it? This was the story that I was born, or adopted, to write. It took me only about 10 months to write it, but four years to get it published. It was rejected by over 60 publishers. When it finally got accepted, I did about three months of extensive rewrites with my editor.

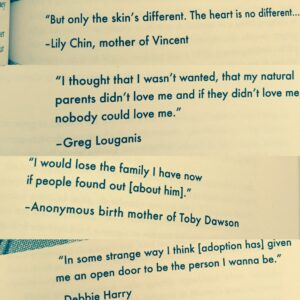

Did you ever keep a list of famous adopted people? I was adopted in 1968 when adoption was still something of a dirty secret. Of course, I couldn’t hide that I was adopted, because I didn’t look like the rest of my family, but those were still early years for transracial adoption. I didn’t meet another adoptee until I was in 8th grade, and was in my 20s before I met another transracial adoptee. Growing up, it felt like I was the only adopted person in the world, so when I heard about other adopted people, I remembered them. Many of the famous adopted people in the book aren’t really that famous—you probably hadn’t heard of some of them. But they were names I had collected growing up to make myself feel a little less lonely.

I know that this is your first published novel but is it the first novel you’ve written? This is my third novel. The first is unpublishable and unreadable, but it was not all for naught for it taught me a lot about the complexities and challenges of writing a novel. For me, in order to get 100 good words, I have to write 1000. All writing is productive, even the stuff that gets deleted because writing is a difficult craft that must be practiced, just as a star pianist practices scales. The second novel was a historical fiction based in Japan. I’m still hoping to get it published!

We have fewer transnational adoptions because the laws here in Australia are very different from those in the US, but in the 1970s around 300 Vietnamese babies came to Australia (“Operation Airlift”) and were adopted by Australian families. Academic Indigo Willing was one of these babies and is now the convener of Adopted Vietnamese International. There’ve been a few current affairs and magazine stories here and there over the year [mainly tabloid stories about celebrities who adopt children from third world countries such as Angelina Jolie and Madonna] but I don’t recall reading a novel from an adoptee’s perspective. I read Emily Prager’s book a while ago but that was a memoir from a mother’s perspective and I very recently read Peter Ho Davies’s short story “Disorientalisation”, which is told from the parents’ perspective. There’s also Ho’s story about Vincent Chin told from a friend’s perspective. What you said in your epilogue that adoptees are characters in other people’s stories rings true in that few stories are told from the adoptee’s point of view. Have you read many other stories written by transnational adoptees?

We have fewer transnational adoptions because the laws here in Australia are very different from those in the US, but in the 1970s around 300 Vietnamese babies came to Australia (“Operation Airlift”) and were adopted by Australian families. Academic Indigo Willing was one of these babies and is now the convener of Adopted Vietnamese International. There’ve been a few current affairs and magazine stories here and there over the year [mainly tabloid stories about celebrities who adopt children from third world countries such as Angelina Jolie and Madonna] but I don’t recall reading a novel from an adoptee’s perspective. I read Emily Prager’s book a while ago but that was a memoir from a mother’s perspective and I very recently read Peter Ho Davies’s short story “Disorientalisation”, which is told from the parents’ perspective. There’s also Ho’s story about Vincent Chin told from a friend’s perspective. What you said in your epilogue that adoptees are characters in other people’s stories rings true in that few stories are told from the adoptee’s point of view. Have you read many other stories written by transnational adoptees?

Yes, that goes back to the reason why I wrote Famous Adopted People. There were all these novels about adoption being published, none of them written by adoptees, all making the adoptee the object of the story rather than the subject. I thought publishers would be eager for an authentic story that didn’t cater to stereotypes, but in the end, it seemed like they were comfortable with the stereotypes and had no interest in changing or challenging the popular notion of the adoption narrative. Also, if you google adoption blogs or browse adoption sections in bookstores, you will see the majority of the offerings are written by and for the adoptive parents. As I say in my novel, everyone is telling our stories but us. But it’s not for lack of trying, I don’t think. I’ve talked to other adopted authors who struggled to get their writing on adoption published.

Not all non-adopted authors who write about adoption get it wrong. I wrote a blog post on 4 novels that get adoption right, and one of them was Peter Ho Davies’ The Fortunes. The chapter to which you refer, which in America was titled “Disorientation,” was really notable to me for bravely and honestly pondering the dilemmas and complexities of transracial adoption. Because the narrator is Chinese-American, he can see the ethical implications of their impending adoption of a Chinese baby that his Caucasian wife cannot.

As for books written by transnational adoptees, there is a website called Adoptee Reading that features books by adoptees. According to them in 2018 two novels by adoptees were published, both by Korean adoptees, one of which was mine, the other Keurium by J.S. Lee, which I highly recommend for a compelling, honest, beautifully written story about one adoptee’s struggle to seize control of her own life. Another Korean adoptee, Julayne Lee has written a powerful, no-holds-barred memoir in poems, Not My White Savior. And Matthew Salesses, who was also adopted from Korea, wrote The Hundred-Year Flood, which is on my list of books to read. But considering that there are hundreds of thousands of transnational adoptees, there should be more representation of our voices in publishing, especially given the popularity of the subject.

I also really liked the book because there’s so much pressure to be a model minority, and I’m sure the pressure is even greater for an adoptee— so it was great to have a [broadly Asian] protagonist isn’t perfect juxtaposed with one who is more stereotypically “Asian”. I think one thing that was lacking when I was younger were stories about women for starters, and then women who I in some way could identify with. I think Anne of Green Gables was the closest. Although these days you have youtube and blogs, these formats are shorter and don’t allow for that space for deeper contemplation which is why I really liked your book. It was fun and I kept turning the pages, but the ideas explored, i.e. race, ethnicity, cultural belonging, genetic legacies, stereotypes, stayed with me long after. In the book Mindy suggests to Lisa she writes in her own voice and her own story, but Lisa retorts that all she knows are white men stories. I could really relate to this line. Growing up as a transracial adoptee, I did recognize myself in books because I thought I was white! I didn’t see any difference between me and Laura from Little House on the Prairie or Darrell Rivers of Malory Towers. And so I didn’t miss seeing myself in books. To me, one of the great gifts of being a transracial adoptee is that I can see myself in everyone. It is always my first inclination to identify with the protagonists, no matter how awful they may be.

It wasn’t until I embraced my Asian identity that I found both my true voice and my message.

What is the American literary landscape like these days for novelists who are [classified] as ‘non-white’? I know that’s a broad question but I guess what I’m getting at is – was it hard to get your book published? As I mentioned before, it took four years and many, many rejections to get Famous Adopted People published. Before Famous Adopted People, I wrote a novel set in Japan during the Meiji era, which was also serially rejected. With Famous Adopted People, though, I didn’t want to let it go. I knew the novel was good, and it was certainly a fresh take on a popular subject, as well as being extremely topical and taking place in ever-fascinating North Korea. When my agent wouldn’t send it out anymore, I submitted it on my own. It was close to a miracle that it was picked out of the slush pile by the perfect editor who knew just what I needed to do to make it into the novel that you enjoyed reading.

In the rejections from editors, there were some coded reasons, like readers don’t like to read about foreign locations or characters with foreign names. Also, the main female characters of both manuscripts were sometimes deemed unlikable (the horror!). So I’d say there is a certain market for Asian-American writers in the mainstream publishing world, but unfortunately, the preference is for silk-and-jade historical fiction rather than a thought-provoking work that sometimes makes people feel uncomfortable. Which isn’t to say that there aren’t a lot of great writers of color being published. But do I think that it’s more difficult to get published as a person of color than as a white person? Yes. And that won’t change until the upper echelons of the publishing industry become more diverse.

Also, another thing I was thinking about when I was coming up with questions for you is whether or not you would fall into the ‘Culturally and Linguistically Diverse’ (CALD) category, one which is one that I can sometimes claim because I was born in a non-English speaking country and am culturally diverse because I’m non-Anglo-Celtic. Yet in other contexts, I’m not because although English is not my mother tongue, it’s the only language I have native speaker fluency in, and I’ve lived in English speaking countries most of my life. Are American categories for ‘diversity’ less confusing? This is the first time I’ve heard of a “culturally and linguistically diverse” category, which seems to be used in the educational field here in the US (I found out when I googled it), but is not widely used by the general public. American society is hypersensitive to race, which is what happens when slavery is written into the founding document of the country. Many official forms have a section where you fill in your ethnicity, and I always used to check Asian and, if they let me choose another one, Caucasian. But last year, I took a DNA test and found even that wasn’t right because I am 19% Native American from Mexico. So now I can check four boxes, Asian, Native American, Hispanic and Caucasian. But really, there are two kinds of people in the US: whites and non-whites. Then, there are other non-race diversity labels, like LGBTQ+, the physically and mentally handicapped, etc. So diversity can be confusing, but basically, it applies to everyone who isn’t a cis-gendered, able-bodied, white male.

I’ve asked most writers with a self-claimed or imposed ‘Asian’ identity this question: Where are you positioned as an American writer or as an Asian-American writer, if at all? Part of the journey of a transracial adoptee is to make that transition from a white identity to an ethnic identity, and learn how to become, as in my case, an Asian-American. The first novel I wrote had a white male protagonist and most of the characters were white. There were no Asian characters in the book at all. That was because at the time I wrote it, I still essentially viewed myself as white. It wasn’t until I embraced my Asian identity that I found both my true voice and my message.

Do you have a regular writing routine? If so what does it look like? Basically, I take a nice, contemplative walk with my dog in the morning, trying to clear my mind of extraneous thoughts and think about what awaits me for my writing day. I write, have an early lunch, write some more and then go swimming. Swimming is very boring, so I take that opportunity to review what I’ve worked on and try to solve problematic points. If so inspired, I may return to writing in the evening. As a writer, you are your own boss, which has extreme advantages but can also mean you feel obliged to write on weekends or after hours when most people have stopped working.

Who or what are some of your other influences? I’ll try to be brief, as there are so many. The two seminal books from my younger years are Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland and Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. In college, I continued to love Conrad, and also fell hard for Thomas Hardy, especially The Mayor of Casterbridge. More recently, I’ve swooned over Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale for the Time Being, Esmé Weijun Wang’s The Border of Paradise, Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer, Han Kang’s The Vegetarian, Caroline Bock’s Carry Her Home, and Jessie Chaffee’s Florence in Ecstasy. I’m a big fan of Chang-rae Lee, Margaret Atwood, Kazuo Ishiguro, and Toni Morrison, to name just a few.

I love all the arts and find inspiration from the way a photograph, song, statue, painting, even a piece of clothing can tell a story. And of course, the natural world endlessly fascinates.

As a writer, you are your own boss, which has extreme advantages, but can also mean you feel obliged to write on weekends or after hours when most people have stopped working.

Did you have a mentor who helped you at the earlier stages of your writing career? I did not have a mentor in my earlier years, and neither did I seek one out. I was determined to do it all on my own, which is foolish. Now, I have writing friends whom I rely upon for advice and feedback. I think one of the most important things an aspiring writer can do is find a strong, supportive writing community.

Before I move onto questions that may include spoilers, what’s next? Currently, I am working on a historical fiction novel on the Japanese-American artist Isamu Noguchi and his experience in an American internment camp.

***Spoiler Alert! Don’t read on if you haven’t read the book!!!!! ***

Are you worried about Jonny reading the book and setting his agents on you and should I be securing my website now that I’ve interviewed you? Wow, if Jonny read my book that would mean that word has really gotten out! But at this point, the book has not generated a lot of coverage or entered the public discourse, so I don’t think I need to worry. However, it has been suggested that I stay away from the beaches for the time being.

I laughed raucously at the part where we find out that Jonny had plastic surgery to look more Korean —albeit very nervously because of the way everyone else’s face was modified— because it’s usually the other way around. i.e. East Asians undergoing surgery to look more Western and being valued for looking more Caucasian! Yes, I wanted to turn the tables a little bit on that. Plastic surgery is alarmingly prevalent in South Korea, which has the highest rate per capita in the world. It is also fast gaining popularity in China. The most popular is blepharoplasty to get the double eyelid. Skin whitening is also hugely popular. Now, imagine if white people started to get surgery to look more ethnic…

Also, another character that made me think ‘wow, this is so different from other books I’ve read’ is Cookie. I’m sure this is one of the few narratives where the pedophile isn’t depicted as pure evil and as a side-line character. When Lisa thinks about killing him, I feel sorry for him and was relieved when she didn’t. It’s really unsettling. It’s like one of those, ‘Ookaay…so you’re stuck in a bunker during a zombie apocalypse’ WWYD hypotheticals. At any point did you or your editors think about removing him from the collective of odd bods in Honey’s circle? My editor never suggested taking Cookie out and it never crossed my mind. With all the other deviants and narcissistic sociopaths, he’s just one of the crowd. But I did get a tsk-tsking review where I was berated for not coming out more forcefully against pedophilia. But this is a work of literary fiction, and I do not have to make absolute declarations like that. I think most discerning readers understand that I’m not condoning pedophilia. I tried to make all the characters human, which means they have good points and bad points. Even Jonny is a bit likable sometimes.

Although I asked you in jest whether you worry about Jonny, were you or your publishers at any stage worried about lampooning him? Or have simply watched too many episodes of shows like Homeland? (I’m not sure Homeland has been set in Asia). Neither my publisher nor I were concerned about including the character of Jonny. There are lots of bigger threats to his regime than my book. But I certainly won’t be planning a trip to North Korea.

How much research did you do for the North Korean parts of your book? I had long been fascinated with North Korea, and read many of the prison camps and escape memoirs like Kang Chol-Hawn’s The Aquariums of Pyongyang, Blaine Harden’s Escape from Camp 14 and Yeonmi Park’s In Order to Live. I also read history and social culture books, like B.R. Myers’ The Cleanest Race, Barbara Demick’s Nothing to Envy, and Bradley Martin’s Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader. One of the best books about the extreme weirdness of the Kim regime is Paul Fischer’s A Kim Jong-Il Production—it was a valuable resource for me. I also watched documentaries and searched youtube for eyewitness accounts of life in North Korea.

You can find Alice on Twitter: @AliceKSStephens, FB: @AliceStephensAuthor, IG: AliceStephensBooks Website: famousadoptedpeople.com

**

Here is a YouTube video about American defectors to North Korea. I watched this after I first read Alice’s book and if I’d known about James Dresnok earlier, I would have asked Alice if she had his story in mind when she wrote the book.

One Comment

Lynelle

Awesome to read about your book and life … thnxs for sharing.

You might be interested to read out two Australian books by intercountry adoptees telling their own stories of adoption.

The Colour of Difference (2001) and The Colour of Time (2017) .. these follow the lives of intercountry adoptees in Australia over 15 years ..

And this huge list of adoptee written books https://intercountryadopteevoices.com/adoptee-voices/adoptee-written-books/